It's that time of year. Your inbox fills with trend reports. LinkedIn floods with predictions. Every vendor publishes their take on what's coming. You bookmark them with good intentions, knowing most will sit unread.

We did the reading for you:

- McLean & Company HR Trends 2026 Report

- Blanchard 2026 HR/L&D Trends Survey

- Degreed: Top 7 L&D Trends for 2026

- Training Industry: Trends 2026

- TalentLMS 2026 L&D Benchmark Report

- D2L Employee Training Statistics 2026

- Josh Bersin Company 2026 Imperatives

- HowNow: Future of L&D Predictions

- Foxtery: 18 L&D Expert Predictions

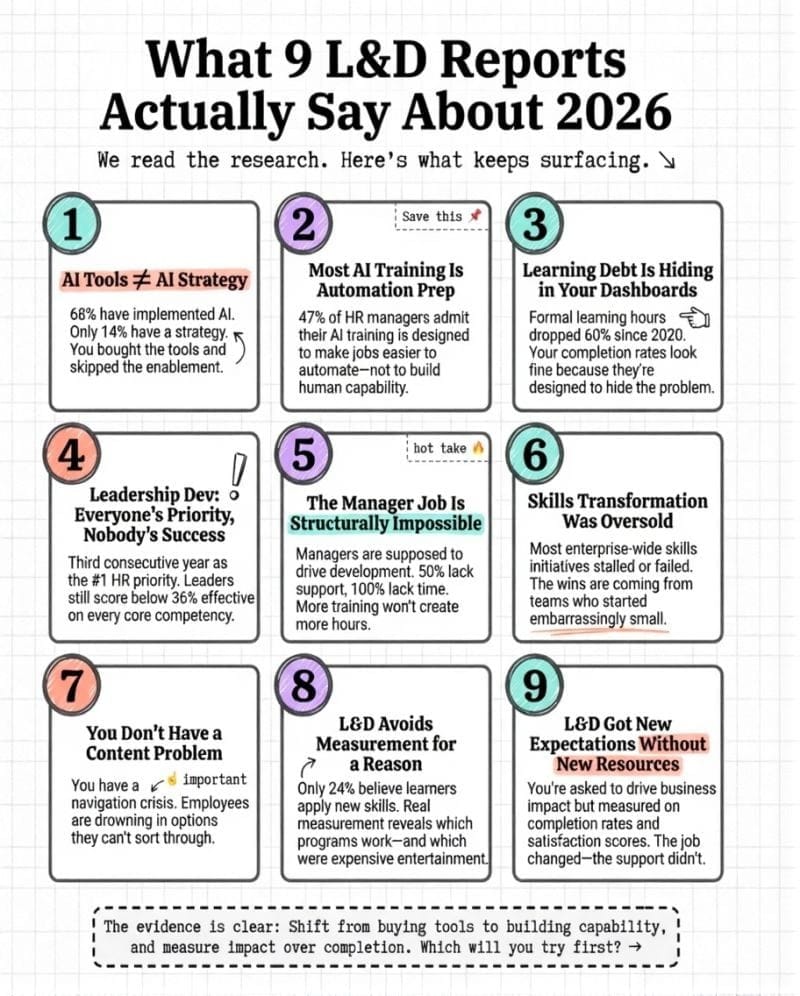

The same patterns kept surfacing across sources. So did the same tensions everyone seems to be wrestling with.

That's what we read. Here's what we found, and what it means for your work.

TL;DR

- The AI gap isn't about access anymore. It's about enablement. Most organizations have tools but no strategy for making them work.

- Learning debt is quietly accumulating as work outpaces development. Half of employees say workloads leave no room for training.

- Leadership development remains the top priority everywhere, but leaders are falling short across every basic skill that matters.

- Managers are supposed to drive development but most lack the support, time, or skills to do it. This paradox threatens everything else.

- Skills-based approaches are maturing into practical reality. The organizations seeing results are thinking small and specific, not enterprise-wide transformation.

1. The AI enablement gap is the story of 2026

Every report mentions AI. Most celebrate adoption rates. Few mention what happens after the rollout.

68% of organizations have moved beyond exploration into implementation, according to McLean & Company. But only 14% have a formal AI strategy. Degreed found that 95% of businesses see zero ROI on their in-house AI investments. D2L's research shows 64% have AI tools, while only 25% have a clear vision for using them. And 56% of employees report being left to figure out AI on their own.

Organizations bought the tools. They skipped the enablement.

A lot of AI training isn't designed to make employees more capable. It's designed to make their jobs easier to automate. TalentLMS found 47% of HR managers admit their company's AI training is aimed at making jobs easier to automate. That's not a skills investment. That's a transition plan that employees are unknowingly participating in.

Meanwhile, 36% of employees say GenAI tools are already weakening their ability to solve problems on their own. The tools meant to augment human capability are quietly eroding it. Most organizations aren't tracking this tradeoff because they're too busy celebrating adoption metrics.

Josh Bersin calls 2026 "The Year of Enterprise AI" and describes a shift from assistants to agents to solutions. But capability, not access, determines whether technology creates impact. The organizations winning with AI aren't the ones with the most tools. They're the ones being honest about what they're training for.

How to close the enablement gap:

- Audit usage before adding tools by surveying how employees interact with existing AI capabilities. Most organizations have more access than adoption.

- Build AI judgment, not just AI skills by designing learning experiences that develop critical thinking about when to use AI, when to override it, and how to evaluate its outputs.

- Be honest about the goal by distinguishing between training that builds human capability and training that prepares roles for automation. Both might be necessary, but pretending they're the same thing is dishonest.

- Track capability, not just efficiency by measuring whether people are getting better at their jobs or just faster at the parts that will eventually disappear.

2. Learning debt is silently accumulating, and most L&D metrics hide it

TalentLMS introduced a concept this year that deserves more attention: learning debt. Like technical debt in software, it describes what happens when organizations take shortcuts on development to deliver faster today. The cost compounds over time.

Half of employees and half of HR managers say high workloads leave little room for training, even when it's needed. Sixty-five percent of employees say performance expectations have risen. ATD's State of the Industry found that formal learning hours dropped from 35 per employee in 2020 to just 13.7 per employee in 2024. Meanwhile, multitasking during training has hit 70%, up from 58% the year before.

Most L&D dashboards are designed to hide this problem rather than reveal it. Completion rates can look healthy while actual capability quietly degrades. Satisfaction scores stay high because people are relieved to get back to "real work." The metrics that make L&D look good are often the same ones that mask how little learning is happening.

Nearly half of employees and HR managers agree their company views training as time away from "real" work. That's not a perception problem. That's an accurate read of how most organizations operate. When your calendar is stacked with back-to-back meetings and your performance review doesn't mention development, you learn exactly what the company values. Training isn't it.

Do the math: if formal learning hours have dropped 60% since 2020 while the pace of change has accelerated, organizations are building a capability deficit they can't see on any dashboard. By the time the gap becomes visible in performance problems, customer complaints, or competitive disadvantage, the debt has compounded beyond what a training program can fix.

How to start paying down learning debt:

- Protect learning time the way you protect meeting time by blocking calendar time for development and making managers accountable for honoring it.

- Redesign for distraction by accepting that 70% of people are multitasking during training and building content that works anyway. Shorter modules, clear stopping points, immediate application.

- Make development a deliverable by including skills growth in performance expectations, not as a nice-to-have but as something people are evaluated on.

- Build metrics that reveal debt, not hide it by tracking where knowledge gaps show up in errors, rework, escalations, or customer issues. Connect the dots between skipped training and downstream problems.

3. Leadership development tops every priority list, but still isn't working

Every report, without exception, names leadership development as a top priority. Blanchard's survey shows that 69% rank developing leadership bench strength as their primary HR objective. Leader and manager development is the number one HR priority for the third consecutive year. Leadership readiness separates organizations that thrive from those that struggle.

McLean & Company's data reveals how wide the gap is. Leaders are falling short across the basics: only 36% highly effective at change management, 26% at talent development, 24% at talent management, 19% at employee engagement. These aren't edge cases. These are core leadership functions.

Most leadership development fails because it's designed to check a box, not change behavior. Organizations send people through programs, add credentials to their profiles, and declare them "developed." Nobody follows up six months later to see if anything changed. The program was the goal, not the outcome.

The data on what works keeps getting ignored. McKinsey found that when continuous learning culture exists, leaders become 5-6x more likely to be highly effective. McLean's research shows that when leaders are held accountable to organizational values, they're 3.2x more likely to make aligned decisions. The lever isn't the training content. It's the system around the training.

But continuous development is harder to budget for than an annual program. Accountability requires difficult conversations. Behavior change means admitting the current leaders might not be as developed as their titles suggest. It's easier to keep buying programs and hoping something sticks.

The reports agree on what leaders need: coaching ability, communication skills, adaptability, change leadership. But most organizations aren't built to develop these capabilities because they've optimized for everything except the conditions that make development stick.

How to make leadership development work:

- Stop treating programs as proof of development by measuring behavior change and business outcomes, not completion certificates and participant satisfaction.

- Build accountability into the system by making leadership effectiveness visible, tying it to performance reviews, and creating consequences for leaders who don't develop their teams.

- Invest in the unsexy fundamentals like giving feedback, running effective meetings, and having difficult conversations. These basics drive more impact than advanced frameworks but get less budget because they're harder to package.

- Extend the timeline by designing development as an 18-month journey with checkpoints, not a 2-day workshop with a follow-up email.

4. The manager paradox is structural, not solvable with training

Managers are supposed to be the primary drivers of employee development. But managers themselves are overwhelmed, undersupported, and often underskilled for this responsibility.

Manager-driven development support is declining year over year. D2L found 50% say managers lack proper support, while 45% say employees lack support. Blanchard identified dissatisfaction with leadership quality as a top retention challenge, alongside burnout and limited career growth.

The math doesn't work. And more training won't fix it.

Organizations have spent the last decade expanding manager responsibilities while shrinking manager capacity. Spans of control grew. Administrative burden increased. Individual contributor work got layered on top of people management. Now we're surprised that coaching and development fall through the cracks.

The reports keep recommending the same solutions: train managers to be better coaches, give them tools and templates, hold them accountable for development. But they're solving for the wrong constraint. The problem isn't that managers don't know how to coach. It's that they don't have time to coach. Giving an overwhelmed person more skills doesn't create more hours in their day.

This is why so many L&D investments underperform. You can build beautiful learning experiences, but if managers don't create space for development, reinforce new skills, or connect learning to work, the investment evaporates. The manager is the bottleneck, and the bottleneck is structural.

Something has to come off the manager's plate before development can go on it. That might mean smaller teams, fewer meetings, less reporting, or accepting that not every manager can be a coach. Pretending managers can do everything with enough training is the expensive fantasy most L&D strategies are built on.

How to address the manager bottleneck:

- Audit the actual manager job by listing everything managers are expected to do, then cutting 20% before adding anything new. Every additional responsibility needs a corresponding reduction.

- Create different manager tracks by acknowledging that some managers will be strong coaches while others will be strong operators. Stop expecting everyone to be both.

- Build peer support structures so managers can learn from each other and share tactics. Isolation makes impossible jobs feel even more impossible.

- Measure what matters by tracking whether managers are having development conversations and whether their teams are growing, then making those metrics as visible as revenue and delivery.

5. Skills-based approaches work when organizations admit they were oversold

The skills conversation has matured. A few years ago, it was about enterprise-wide skills-based organization transformation. Now the research shows a more honest picture: most of those transformations stalled or failed.

Nelson Sivalingam captured the shift well: "skills with a little s" rather than capital-S transformation. Focus on what skills people need to do their current job well and stay ready for the next one. Not a multi-year taxonomy project. Not a complete restructuring of how you think about talent.

TalentLMS found 79% of HR managers say their company is adopting skills-based approaches. But building a truly skills-based ecosystem is more complicated than it sounds. It requires clean data, consistent frameworks, and the time to map roles, competencies, and learning content. The vision of agile, skills-driven organizations hasn't disappeared, but it's clear that most teams were too ambitious, too soon."

The organizations making progress are the ones that ignored the comprehensive approach entirely. They didn't build enterprise-wide taxonomies. They picked three skills that mattered for one team, got specific about what "good" looks like, and built from there.

The skills gap isn't shrinking anyway, just shifting. The World Economic Forum projects 39% of core skills will change by 2030. Organizations have made progress on basic digital literacy, but gaps are widening in strategic thinking, leadership, and adaptability. The easy skills get automated. The hard ones are what's left. And those hard skills resist the tidy taxonomy approach that made skills transformation feel manageable.

How to make skills-based approaches practical:

- Start embarrassingly small by picking one team, three skills, and a 90-day timeline. Prove the approach works before scaling.

- Define skills in observable terms that describe what people do, not competency language designed to sound impressive in a framework document.

- Skip the taxonomy project by building skills definitions as you need them rather than trying to map everything upfront. Comprehensive approaches usually die before delivering value.

- Connect skills to actual opportunities so employees see a direct link between building specific capabilities and getting access to projects, roles, or promotions that matter to them.

6. Content abundance created a navigation crisis

Content is everywhere and getting cheaper by the day. AI can generate a course in hours. Every vendor has a library of thousands of offerings. Employees have more learning content available than they could consume in a lifetime.

And yet, "finding the right training content" remains among the top obstacles for L&D teams.

This is the navigation crisis. Organizations built extensive catalogs, assuming that more choice would lead to better outcomes. Instead, employees face an overwhelming wall of content with no clear guidance on what to take, when to take it, or how it connects to their goals. D2L's research found the problem isn't limited access. It's that people don't know which direction to go.

The reports describe the shift happening: Degreed predicts libraries will become raw materials for AI-assembled personalized pathways rather than destinations. Training Industry describes content becoming an ingredient, not a product. The value isn't in what you have. It's in connecting the right content to the right person at the right moment.

But most L&D teams are still measured on content production and catalog growth. The metrics reward building more, not connecting better. Teams keep creating new content while employees drown in options they can't navigate.

Karl Kapp's question from the Foxtery roundup highlights this: "What does the employee need to do on Tuesday at 10:15 a.m.?" If your content strategy doesn't answer that question in under 30 seconds, you've built a library, not a learning system.

How to shift from content production to content connection:

- Stop measuring catalog size by removing any metrics that reward having more content. Start measuring content utilization, search success rate, and time-to-answer.

- Build navigation, not just content by investing in curation, tagging, and pathways that help employees find what they need. The librarian role matters more than the author role.

- Kill before creating by establishing a rule that every new piece of content requires retiring an old one. Force the trade-off between quantity and quality.

- Design for the Tuesday morning question by organizing content around moments and tasks rather than topics and competencies. What do people need to do?

7. The measurement problem reveals what L&D is afraid of

Blanchard's survey found that only 29% believe current measurement practices clearly demonstrate L&D's value. Only 24% believe learners apply new skills "to a large extent" or better. Nearly half view their measurement as only "somewhat effective."

The reports frame this as a capability gap. L&D teams need better analytics, better tools, and better connections to business data. But that diagnosis misses the deeper issue.

Most L&D teams don't measure outcomes because they're afraid of what the data will show.

When you measure completion rates, the numbers look good. When you measure satisfaction, people are happy to be done. When you measure behavior change six months later, you discover that most training didn't stick. When you connect learning to business results, you find that some programs delivered impact, while others were expensive entertainment.

Real measurement creates accountability. It reveals which programs work and which don't. It shows which facilitators drive results and which just get good evaluations. It makes it harder to keep doing what's comfortable and easy to budget.

Training Industry emphasizes connecting learning outcomes directly to organizational performance, like internal mobility, promotions, and retention. The organizations proving L&D's value aren't the ones with better dashboards. They're the ones willing to know the truth about their impact.

There's also a misalignment between what L&D measures and what executives care about. Sixty-five percent of HR managers say employee engagement is their top success metric. But executives want to see productivity, performance, and business impact. L&D keeps measuring what makes them feel good while wondering why they struggle to get budget and strategic influence.

How to measure what matters:

- Start with the outcome you want by defining what business result this program should influence before building anything. Then work backward to design measurement.

- Measure behavior change at 30, 60, and 90 days by tracking whether people do something different after training, not just whether they remember what was taught.

- Connect to metrics executives already watch by tying learning to revenue, customer satisfaction, quality, or speed. Stop inventing L&D-specific metrics that only L&D cares about.

- Embrace the data that stings by accepting that measuring outcomes will reveal some programs don't work. That's information, not failure.

What the research agrees on

Across these reports with different methods, angles, and audiences, the same themes keep surfacing:

- The AI conversation has moved from adoption to enablement. Having tools isn't the bottleneck anymore. Knowing how to use them well is. And a troubling amount of AI training is quietly designed to automate roles rather than augment them.

- Time and space for learning are eroding. Workloads are up, development is squeezed, and most L&D dashboards are designed to hide this problem rather than reveal it.

- Leadership development matters more than ever but keeps failing. Everyone agrees it's the priority. Most programs don't change behavior because they're designed to check boxes, not build capability.

- Managers are the key to making development work, and the biggest barrier. More training won't fix a job that's designed to be impossible. Something has to come off the plate before development can go on it.

- Skills-based approaches are maturing because organizations gave up on transformation. The wins are coming from teams who ignored the enterprise-wide vision and started embarrassingly small.

- Content abundance created a navigation crisis. The problem isn't having enough. It's that nobody can find what they need when they need it.

- Measurement avoidance reveals what L&D is afraid to know. The organizations proving value aren't the ones with better dashboards. They're the ones willing to find out which programs work.

L&D is being asked to drive strategic impact while operating with operational constraints and success metrics designed for a different era. The reports describe what's changing. Whether your organization is willing to change how L&D operates, not just what it produces, is a different matter.

Every report agrees that the future belongs to learning that's embedded in work, personalized to the individual, and connected to business outcomes. Getting there requires dismantling most of what L&D teams currently do. The question isn't whether the vision is right. It's whether anyone has the courage to build it.